CYCLOPS & CLOUDS

Coming to The Cockpit theatre 16th-20th September 2025

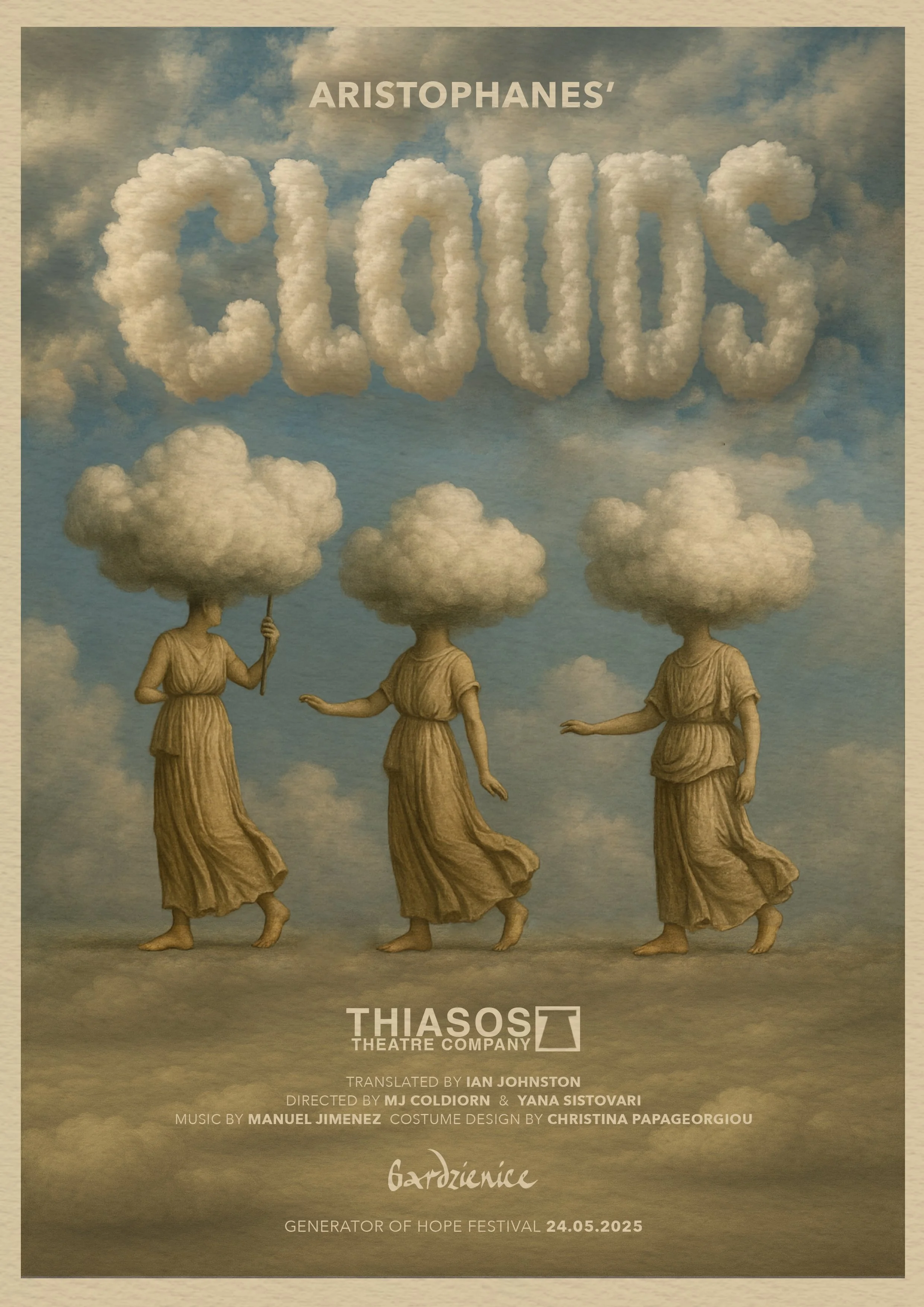

Thiasos returns to The Cockpit with a fabulous double bill of Euripides' CYCLOPS, the only surviving satyr play from Ancient Greece, and Aristophanes' CLOUDS--a satirical take on the uses and misuses of academia and argument. Both shows have received rave reviews and feature the brilliant singing and dancing choruses that are the company's trademark, with new original music by Manuel Jimenez. Don't miss this opportunity to see these two rarely-performed masterpieces!

Euripides' CYCLOPS (translated by J. Michael Walton) tells the story of Odysseus and his battle with the monstrous Cyclops Polyphemus, helped by a chorus of wine-loving satyrs--half men, half goats.

It opens on Tuesday, 16 September at 8.30 pm and can be seen again on Thursday, 18 September at 8.30 pm, Friday, 19 September at 6.00 pm, and Saturday, 20 September at 7.30 pm

Aristophanes' CLOUDS (Translated by Ian Johnston) pits the philosopher Socrates against a wily farmer who is overburdened with debts and wants to learn to beat his creditors in court. They both learn from the changeable chorus of Clouds that making the Worse Argument can get you into a stack of trouble.

CLOUDS has its London premiere on Wednesday 17 September at 8.30 pm and can be seen again on Thursday 18 September at 6.00 pm, Friday 19 September at 8.30 pm and Saturday 20 September at 3.00 pm.

Renowned classics scholar and media star Professor Edith Hall will give a post-show talk with Q&A on Wednesday, 17 September.

On Friday 19 September, Professor Fiona Macintosh, Emeritus Professor of Classical Reception, Senior Research Fellow of St. Hilda’s, Oxford and former director of the Archive of Performance of Greek and Roman Drama will be discussing both plays between the shows at 7.30 pm.

Join us at The Cockpit!

PROGRAM NOTES

Will Socrates stand up?

An oft-quoted anecdote claims that during the original performance of Aristophanes’ Clouds (423 BCE, with a revised version c. 420 BCE), Socrates himself was in the audience. When the comic figure of “Socrates” appeared on stage, the philosopher supposedly stood up so that spectators could compare him with the actor. Whether or not this really happened is uncertain: K. J. Dover, the magisterial commentator on Clouds (1968), stresses that the story is late and unreliable.

The ‘Socratic’ Mask

In Aristophanic comedy the mask worn by Socrates was said to have represented him as bald, snub-nosed, with bulging eyes — features associated with satyrs and Silenos figures. Opinion has long been divided. Did Socrates truly resemble this mask, or were such satyric features invented to ridicule him, damage his reputation, or conversely cast him in a paradoxical role, where comic ugliness concealed a deeper wisdom?

This raises two interlinked questions:

1. Did the historical Socrates really look like his theatrical mask?

2. Does the Socrates of Clouds — portrayed as a natural philosopher, sophist, and teacher of dubious rhetorical tricks — resemble the Socrates we meet decades later in Plato’s Symposium and other dialogues?

Socrates in Aristophanes

The Aristophanic Socrates is less a portrait of one man than a composite “intellectual type.” As Dover notes, he is an amalgam of natural philosophers, sophists, and teachers of rhetoric. In the play, he:

denies traditional religion, replacing Zeus with the Clouds;

teaches sophistic methods, dramatized in the debate between the Better and the Worse Arguments;

conducts a mock initiation for Strepsiades, parodying mystery rites;

exhibits a lofty detachment from ordinary concerns.

Socrates in Plato

In Plato’s Symposium (composed some years after Clouds), Alcibiades compares Socrates to a Silenos statue: grotesque on the outside, but hiding images of divine beauty within. The image thus corresponds to the silenic mask. Socrates’ external ugliness is explicitly contrasted with Alcibiades’ own good looks and athletic prowess. In the famous scene, Alcibiades even attempts to seduce him — and fails. Here the ugliness of the silenic mask is inverted into a paradoxical emblem of inner wisdom. Socrates’ “wisdom” is not sophistry but a relentless search for truth, turning the comic caricature on its head.

Crosscurrents on Stage

In our productions the same actor plays both Socrates in Clouds and Silenos in Cyclops. He does not wear a mask, but his natural features resemble a more handsome version of the silenic type. This doubling invites the audience to reflect on the tradition that Socrates himself looked like Silenos. That tradition may not reflect reality, but may instead derive from the visual resemblance between the comic mask of Socrates and the satyric mask of Silenos, as preserved in vase painting. By embodying both figures in one performer, the production crystallizes the ancient tension between comic parody and philosophical seriousness.

From Metaphor to Mask

An important issue emerges here. Ancient intellectual discourse, especially in Plato’s Symposium, developed a symbolic comparison between Socrates’ nature and the Silen figure: ungainly on the outside, yet containing divine treasures within. This was originally a physiognomic metaphor, a way of thinking about character through bodily form. Over time, however, the metaphor may well have hardened into a literal physiognomy. Commentary on Socrates’ thought was translated into an actual mask type: what began as philosophy became stagecraft.

We have both the mask of Silenos (on the famous Pronomos vase) and Old Comedy masks preserved in iconography. These have similarities. The supposed resemblance between Socrates and Silenos may therefore stem not from the philosopher’s actual appearance, but either from a physiognomic metaphor or from the conventions of mask design — a visual coincidence turned into cultural memory.

Theatre as Reflection

The enduring power of theatre is its ability to crystallize centuries of debate within a single performance. By juxtaposing our two plays, we revive important questions concerning not only Socrates’ appearance but also his philosophy and morality.

One Actor, Many Worlds

Theatre reminds us how much one actor can encompass. The same performer may embody Socrates in Clouds and Silenos in Cyclops, holding together parody, philosophy, and pathos. Within a few hours on stage, one body and one voice can bring into focus contradictions that have fascinated audiences and scholars for over two thousand years. This is the wonder of theatre: its power to distill entire histories of thought into the fleeting presence of a single performance.

Philosophers and clouds in Aristophanes’ Clouds

Aristophanes’ Clouds, from which we have extracted our performance, is the partially revised c. 420 BCE version of the original performed in 423 BCE .

Aristophanes was the best known of a new generation of the‘Old Comedy’ poets. He was strikingly and uniquely skilful at building theatre around ideas—at taking a premise and twisting its logic to turn it into a drama with conflict and characters.

Hence our ‘hero’s’ name, Strepsiades, who ‘tosses and turns’ at night, tormented by his debts, is derived from ‘strephei’ meaning ‘twist’); Strepsiades also wishes to ‘twist’ impending lawsuits to avoid paying his creditors. Dikē means justice so strepsodikēsai means, literally, ‘to twist justice’.

The Clouds is exceptional amongst Aristophanes plays (as indeed amongst all the Old Comedy plays) in at least three ways:

It has a plot, a remarkably integrated chorus and an ending which is startlingly alien to the festive spirit of Old Comedy where plays traditionally end in feasting and reconciliation.

The plot tells of Strepsiades, an ignorant peasant driven into debt by his son Pheidippides’ mania for chariot racing. The old man has learnt of a method whereby ‘argument’, as practised in the courts, can pervert reason and truth and twist justice in favour of the wrongdoer. This method is taught—for profit—at the Thinkery, a school run by Socrates where the barefoot, emaciated, pale, flea-ridden students learn about the latest developments in science, philosophy and rhetoric. The traditional Olympian gods have been cast aside in favour of the ambiguous, nebulous chorus of Clouds, and other phenomena such as Vortex, Aether, Chaos and Tongue.

The character of the chorus thus echoes the play’s focus on the trickery of the Sophists and on the absurdities of the natural philosophers.

THE PHILOSOPHERS

The Sophists (such as Protagoras, Gorgias and Prodicus) were known for their relativism, clever argumentation, disregard for tradition and teaching for money. Their methods play a prominent part in the plot that backfires after the hollow victory of clever Wrong Argument over the fusty traditional (and lecherous!) Better Argument leads to the burning down of the Thinkery.

The variety of natural philosophers (dating c. 600 to 400 BCE), known collectively as the Presocratics, share a reputation for seeking natural explanation for the Cosmos, speculating about fundamental substances, and replacing myth and religion with material principles. Specific thinkers such as Thales (known for proposing that water is the fundamental principle of all matter), and Chaerephon (who consulted the Delphic oracle declaring Socrates the wisest man), are mentioned by name. The play however abounds in references to unnamed but specific philosophical speculations. These are mainly presented by Socrates as abstractions, which are then made literal by Strepsiades for comic effect.

Bear in mind that Aristophanes (c. 446-386 BCE) and Socrates (c. 470-399), were living and themselves key players along with the philosophers satirised both explicitly and implicitly.

We cannot be certain of the extent to which the audience grasped the finesses of Aristophanes’ jokes. In the parabasis (a traditional break in the action during which the poet speaks directly to the audience) Aristophanes states overtly that his art is above his critics’ heads.

More controversial is Aristophanes’ portrayal of Socrates. Socrates’ verbal trickery, relativism and replacing of traditional gods with physical explanations is an amalgam of sophism and Presocratic thinking. The (sophistic) argument taught at the Thinkery (that you can justify anything, including beating not only your father, but also your mother) is the last straw: Strepsiades recants and burns down the Thinkery, symbolically rejecting the ‘new’ thinking and returning to belief in the traditional gods.

THE CHORUS

The dissembling, language-quibbling, and intellectual dishonesty of sophistry, are well represented by the physical characteristics of smoke-like, shape-changing, sky-inhabiting clouds. Their role in the play, however, goes beyond the metaphors based on their appearance and on their weather-related properties.

Unusually for Aristophanes’ choruses, these ‘clouds’ are moral agents who are active in deluding Strepsiades and contriving his punishment.

In Greek myth and literature clouds are often active in divine trickery and punishment: in Euripides’ Helen, for instance, it is not the woman Helen herself who was the notorious casus belli of the Trojan war, but rather, a cloud in the image of Helen, sent by Hera to make it seem that the Trojan War had been fought over an illusion. Similarly, Zeus tricked Ixion, who was lusting after Hera, by sending a cloud in her image. Ixion fell into the trap by trying to seduce the ‘cloud’ and so received his legendary punishment of being bound to a wheel of fire spinning eternally in the sky.

In the Clouds, the chorus are invoked as deities by Socrates for Strepsiades’ initiation into the Thinkery in a scene which mocks various secret cults—(Pythagorian, Orphic and possibly Eleusinian mystery cult). The chorus then drifts into sight as a slow majesty of clouds, which have gathered on the mountains, spreading onto the land to shower their benefits of fertility and celebration. The tempo of the entry song is closer to tragedy and very different to the usual entrances of Aristophanes’ choruses.

Even more telling than the music accompanying their appearance is their role in the play: the lyrical beginning changes gradually as the ‘goddesses’ become alienated from Strepsiades and, after maintaining an even hand in the debate between father and son, they foretell disaster and finally approve of the punishment meted out for the injustice he had set out to contrive. This behaviour is more in keeping with tragic choruses who often see in the heroes’ destruction the triumph of the gods’ will.

The jury is out on the significance of the ending. Is it a punishment for undermining traditional morality? Is it Aristophanes’ response to being undervalued? Is it a mockery of academic thought that is increasingly convoluted and detached from reality?

What we do know however is that twenty-four years later the play was used in evidence against Socrates in his trial on charges of blasphemy and corrupting the youth of Athens.

CREDITS

CYCLOPS

By Euripides, translated by J Michael Walton

Music by Manuel Jimenez

SILENOS William Hastings

SATYRS James Jack Bentham

Elliot Windsor

Felix Ryder

Jack Rumsey

ODYSSEUS Salvatore Scarpa

SAILORS Oliver Ellard

Birte Widmann

CYCLOPS Simon Rhodes

Musicians: Manuel Jimenez (violin, mey, percussion); Alexandra Andrei (accordion); Birte Widmann (flute, recorder, halusi, mandolin, percussion); Hannah Shimwell (clarinet)

CLOUDS

By Aristophanes, adapted from a translation by Ian Johnston

Music by Manuel Jimenez

STREPSIADES James Jack Bentham

PHEIDIPPIDES Felix Ryder

SOCRATES William Hastings

THE CLOUDS Birte Widmann

Alexandra Andrei

Jack Rumsey

Elliot Windsor

BETTER ARGUMENT Simon Rhodes

WORSE ARGUMENT Salvatore Scarpa

CHAEREPHON Oliver Ellard

CREATIVES:

CO-DIRECTORS MJ Coldiron, Yana Zarifi-Sistovari

MUSICAL DIRECTOR Manuel Jimenez

Assistant Musical Director Elliot Windsor

DESIGNER Christina Papageorgiou

MOVEMENT/CHOREOGRAPHY Birte Widmann

LIGHTING & TECH DIRECTOR Catherine van der Hoven

COMPANY STAGE MANAGER Maria Cristina Pettiti

WARDROBE MISTRESS/

COSTUME CONSTRUCTION Sao Mourato

CLOUD COSTUME CONSTRUCTION Evangelia Tsiouni

HEADDRESSES & CYCLOPS MASK Dimitra Kaisari

LOGISTICS & CATERING José Mourato